iof2020 From farm to fork

Driving food sustainability using the UN’s 2030 Agenda

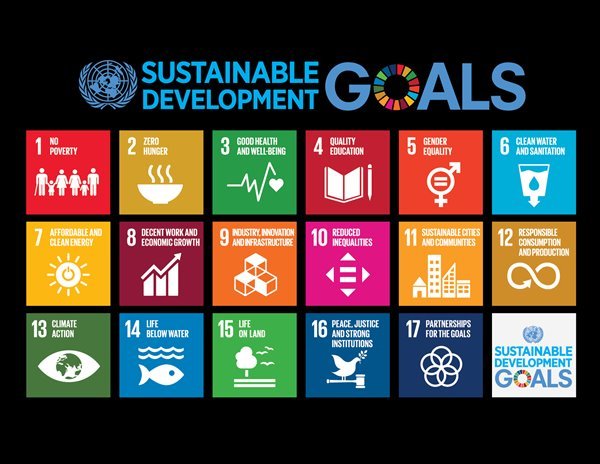

The Sustainable Development Goals as a Proxy for the Farm to Fork Strategy: Our Farm to Fork Bootcamp uses the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a framework to help organisations align with the EU Farm 2 Fork strategy, and strategically position themselves for future funding opportunities like Horizon Europe. Follow our reasoning here.

The EU Farm to Fork Strategy

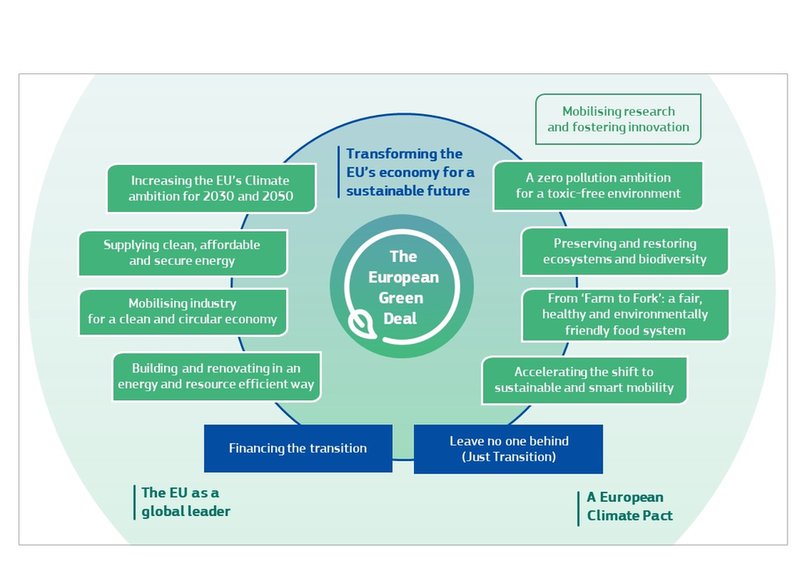

The EU Farm to Fork strategy is part of the EU Green Deal, which builds on the commitment of all European Member states to achieve the SDGs. As such, and just as with the EU Green Deal Calls under Horizon 2020, all Horizon Europe Calls will ask for any call’s contribution to the Green Deal and its corresponding actions. That contribution can be made more apparent using the SDGs.

Explore how this approach can help you align with the Green Deal calls

We believe the SDGs can be effectively used to help align, qualify and quantify a project’s contribution to the EU Green Deal and any of its underpinning strategies. With 169 targets and more than 200 indicators which again have spawned a lot of third party SDG-matched frameworks and strategies, one can use the fact that the SDGs are a common language to describe how one’s work contributes to a sustainable future or a sustainable food system, beyond the EU’s policy frameworks

IoF2020 Use Cases that went through the Bootcamp were able to more effectively align their work to the Farm to Fork strategy, communicate why and how their work is relevant to it and, and create a hypothesis on how to measure the impact their solutions have.

For UC5.3 in the Meat Trial of WP2 I participated in mid of September in the IoF Farm to Fork Bootcamp (two half days) from WP4. The intention of the workshop was to support the exploitation of the results of our use case with the focus on SDG’s by the EU. I found out that it was VERY useful to work together with Nadim and Christian and explore new perspectives on our solution for proactive auditing. A well-structured procedure of the workshop with the group character helped to find out the right sustainability goals with their best fit of corresponding targets and finally completed by a set of KPI. I learned a lot and will use it certainly again in the future

Tim Bartman, GS1 Germany

Use Case 5.3 Partner - IoF2020

Let’s explore the three building blocks of our approach:

The FAO’s latest report on SDG Progress

Future Calls and Horizon Europe

EU Whitepaper

The EU had published a white paper providing guiding principles that explain what is expected from applications for the next Horizon 2020 and Horizon Europe calls.

Among these requirements and expectations for the Horizon 2020 Green Deal calls, we recount:

- Applying system thinking/systems approaches to define the challenge

- Adopting a multi-actor and cross-sectoral approach

- Including the most appropriate mix of innovations

- Where appropriate, federating existing testing and demonstration facilities to strengthen their capacity to address the challenge and showcase solutions.

- Delivering and implementing an action plan for dissemination, communication and engagement

- Test, pilot and demonstrate, across different geographical and sectoral contexts

- The impact of these solutions on the three dimensions of sustainability (social/health, climate/environmental and economic)

- Explain and quantify, using Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

Looking forward, under Horizon Europe, €10 billion will be invested in R&I related to food, bioeconomy, natural resources, agriculture, fisheries, aquaculture and the environment. Knowledge transfer will be essential. The CAP’s farm advisory services and farm sustainability data network will be instrumental in assisting farmers in the transition.

Using the SDGs as a proxy to align with future call requirement can be a differential advantage

The UN Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and improve the lives and prospects of everyone, everywhere. The 17 Goals were adopted by all UN Member States in 2015, as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which set out a 15-year plan to achieve the Goals. behind.

The 17 goals and their 169 targets are integrated and indivisible and balance the three dimensions of sustainable development: the economic, social and environmental.

The interlinkages and integrated nature of the Sustainable Development Goals are of crucial importance in ensuring that the purpose of the new Agenda is realised. If we realize our ambitions across the full extent of the Agenda, the lives of all will be profoundly improved and our world will be transformed for the better.

But perhaps the most important aspect of the interlinkages and integrated nature of the SDGs is the fact that they allow us to approach sustainability challenges from a systemic lens.

SDGs

The SDGs as a proxy methodology can be used to help you align with upcoming Horizon Europe calls. Below, we illustrate how if could have been used to help align with one of the previous EU Green Deal calls under Horizon 2020: Testing and demonstrating systemic innovations in support of the Farm-to-Fork Strategy

Subtopic A. [2021]

Achieving climate neutral farms by reducing GHG emissions and by increasing farm-based carbon sequestration and storage (IA)

Subtopic B.

Achieving climate neutral food businesses by mitigating climate change, reducing energy use and increasing energy efficiency in processing, distribution, conservation and preparation of food (IA)

Subtopic C.

Reducing the dependence on hazardous pesticides; reducing the losses of nutrients from fertilisers, towards zero pollution of water, soil and air and ultimately fertiliser use Proposals have to address all challenges (those related to pesticides, and to fertilisers, and to losses of nutrients) specified under Subtopic C. ]] (IA)

Subtopic D.

Reducing the dependence on the use of antimicrobials in animal production and in aquaculture (IA)

Subtopic F.

Shifting to sustainable healthy diets[12], sourced from land, inland water and sea, and accessible to all EU citizens, including the most deprived and vulnerable groups (IA)

Subtopic E.

Reducing food losses and waste at every stage of the food chain including consumption, while also avoiding unsustainable packaging (IA)

All subtopics (A), (B), (C), (D), (E), and (F):

The proposals should focus on systemic innovations that maximise synergies and minimise trade-offs to deliver co-benefits on the three dimensions of sustainability (climate/environmental, economic, social/health, including biodiversity and animal welfare), that enhance resilience of food systems to various shock and stresses, and that enable them to operate within a safe and just operating space and ensure sufficient, safe, healthy, nutritious, and affordable food for all.

Proposals should pay particular attention to:

- Applying system thinking/system approaches to define the challenge, including an in-depth systemic analysis of its drivers and root causes; to identify possible innovative systemic solutions from production[13] to consumption; to assess their expected and actual impact including risks, synergies, and trade-offs with regards to the three pillars of sustainability (social/health, climate/environmental and economic), food and nutrition security, food system resilience, food safety and the objectives outlined in the Farm to Fork Strategy and the Green Deal.

- Adopting a multi-actor[14] and cross-sectoral approach engaging practitioners (primary producers, processors, retailers, food service providers, consumers), public and private institutions (governmental institutions, NGOs, industry) and citizens from farm[13] to fork to co-create, test and demonstrate solutions from production to consumption, in practice, on a European scale but with attention for regional and sectoral needs and contexts (environmental, socioeconomic, geographical, cultural). Foster collaboration, building bridges and breaking silos between actors of the food chain and between primary sectors as well as collective action. Take specific care to engage young professionals (e.g., young farmers, young fishers, young researchers, young entrepreneurs, etc.), SMEs, consumers and citizens.

- Including the most appropriate mix of innovations, such as novel, digital and space-based technologies using EGNSS and Copernicus data and services, new business and supply chain models, new governance models, ecological and social innovations[16] while taking into account regional and sectoral contexts (environmental, socioeconomic, geographical, cultural) and needs, both for production and consumption. The projects should focus on upscaling innovations (TRL level 5-7), and can include limited research activities to address specific gaps for solution building, testing and demonstration. Particular attention should be given to understand behaviours, motivations and barriers, with a view to maximizing the uptake of solutions. The innovations delivered by the proposals have to take into account the EU market regulatory frameworks (e.g. safety, environmental) and relevant requirements.

- Where appropriate, capitalise on existing testing and demonstration facilities to strengthen their capacity to address the challenge and showcase solutions.

- Delivering and implementing an action plan for dissemination, communication and engagement, for building awareness, education and skills relevant to the solutions on a European scale, in and beyond the regions where the activities take place, among businesses, investors, entrepreneurs, institutions, stakeholders and citizens. Promote their widespread uptake, realize behavioural change, and stimulate investment. Proposals should foresee a dedicated work package for cooperating with European Commission services and with all selected projects under this topic on the implementation of this action plan, with a view to increasing the impact of that plan. Projects may link with other relevant European and national programmes, where appropriate.

Building the Food chain that works for Consumers, Producers, Climate and the Environment

A healthier and more sustainable EU food system is a cornerstone of the European Green Deal, and therefore the 2030 Agenda.

The Farm 2 Fork strategy aims to make that a reality. It addresses comprehensively the challenges of sustainable food systems and recognises the inextricable links between healthy people, healthy societies and a healthy planet.

A sustainable EU Food System should:

- Make sure Europeans get healthy, affordable and sustainable food,

- Tackle climate change

- Protect the environment and preserve biodiversity

- Ensure fair economic return in the food chain

- Increase organic farming

The Green Deal is an integral part of this Commission’s strategy to implement the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals

With the EU Green Deal, the Commission has put the UN Sustainable Development Goals at the heart of the EU’s policymaking and action. Organisations should therefore implement the SDGs as their strategic guiding principles

Goals Green Deal

Climate change and environmental degradation are existential threats to Europe and the world. That is why Europe‘s Green Deal aims for a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy. The goals of the Green Deal are:

- no net greenhouse gas emissions are released by 2050

- economic growth is decoupled from resource use

- no one, neither people nor region, is left behind.

The EU Green Deal includes an action plan to promote more efficient use of resources through the transition to a clean and circular economy and restore biodiversity and combat pollution. The Commission has even proposed the European Climate Act to turn this political commitment into a legal obligation. All sectors of the economy must make an active contribution:

- Investing in new, environmentally friendly technologies

- Supporting industry in innovation

- Introducing cleaner, cheaper and healthier forms of private and public transport

- Decarbonizing the energy sector

- Increasing the energy efficiency of buildings

The EU will provide financial and technical assistance with the transition to a green economy and aims to mobilize at least €100 billion over the period 2021-2027 in the most affected regions

Box 2

Example of an iterative Value Sensitive Design process

making a mobility app for blind people

Conceptual research

In the conceptual research the researchers identified the key stakeholders – both direct and indirect stakeholders - related to applications that support blind and deafblind people in using public transport. Then researchers made a first identification of values at stake in the domain. For this, the researchers used the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities. They also found other values that play a role such as security, trust and privacy. Safety turned out to be very important for the potential users.

Empirical study (1): identifying values

In this phase the researchers conducted 30- to 45-minutes semi-structured interviews with 6 blind adults (2 men and 4 women). The 6 participants gave the highest priority to the values ‘independence’ and ‘trust’. They expressed great concern about ‘safety’. The participants often asked other people for information about their environment, but people who give reliable information are not always present. They preferred to access information on their iPhone or GPS system (in accordance with the importance of independence). But getting the information by speech can be distracting and unsafe or difficult to hear when they are in the bus or train. The present professional specialized supporting technology was expensive and inconvenient to carry.

The researchers also conducted 30-minute semi-structured interviews with 7 deafblind adults (4 men, 3 women) and an instructor who provides orientation and mobility training to deafblind people. As with the blind participants, the values of independence, trust and security were prioritized/highlighted in the interviews. All deafblind participants and the instructor associated access to information with the values security and trust. This information is about a person's physical environment (e.g. trees in the middle of sidewalks), bus arrival times, upcoming bus stops and communication with the driver.

The researchers also included bus drivers in the conceptual study because they are the main indirect stakeholders for the technology application. The bus drivers who accidentally transport the blind and deafblind are responsible for the safe arrival at their destination. The researchers sent a survey on drivers' opinions and values to 500 bus drivers. The surveys were completed anonymously. The response was 47%. The survey mainly focused on real-time switching information tools. Part of the survey included questions about passengers who are blind or deafblind. The researchers coded the answers by grouping them into positive, neutral and negative feelings about the carriage of blind or deaf-blind passengers. With few exceptions, responses were very positive.

Technical investigation

Assess current technology

Already in the former empirical research phase, the researchers described current technology, including GPS systems, Braille annotation devices and wearable communication devices especially for deafblind people. These technologies give access to information that provides a certain degree of independence for blind and deafblind people. Other values that were important to the participants were not yet supported by current technology, such as affordability and comfort. Blind participants said that information in Braille had several advantages over information in speech. But deafblind participants have no speech and therefore need Braille devices.

The MoBraille Framework

To better support the identified values, the researchers designed a system that allows blind and deafblind people to access information via Braille on a small, regular smartphone. The system was called MoBraille ("mobile braille").

GoBraille for the blind in public transport

The researchers also developed a MoBraille application (called GoBraille) for the blind that enabled them to get information about (1) the nearest intersection and address, (2) real-time bus arrival for nearby stops and (3) non-visual landmarks and specific location information about nearby stops. In addition, the researchers have also developed a version of GoBraille for deafblind people that gives them real-time information about the bus arrival at his or her current stop. Based on iterative feedback from a deafblind participant, the researchers simplified the interface for deafblind people.

Empirical study (2): evaluating the designed technology applications

Evaluation of GoBraille for the blind

The researchers had GoBraille assessed by 10 blind adults who regularly rode the public transport bus. The evaluation focused on the new aspects of the GoBraille. The evaluation was conducted on a sidewalk of a busy street and near several bus stops. After the researchers explained how the GoBraille application worked, the 10 blind participants were given several tasks to perform using the application. When the tasks were completed the researchers conducted a 20-minute semi-structured interview with the 10 participants. The aim of the interview was to determine how the access to GoBraille’s various information sources would affect a participant's sense of independence and security when using public transportation. The researchers wanted to know how the input and output in Braille interacted with the system. It turned out that the participants were very satisfied with the system.

Co-design with a blind-deaf person

The researchers developed a version of GoBraille for deafblind people by working with a deafblind person who used the bus regularly. This happened in 3 sessions of 1.5 hours each. In each design session several problems emerged. The lessons the researchers learned from this co-design process have been translated into three general guidelines that can be used for designing such applications.

Source: Azenkot, S., S. Prasian, A. Borning, E. Fortuna, R.E. Ladner, J.O. Wobbrock, 2011. Enhancing Independence and Safety for Blind and Deaf-Blind Public Transit Riders. CHI 2011. Vancouver, BC, Canada.